By FRED KRONER

In China, 2022 is the Year of the Water Tiger.

In the United States, it is the year to remember and celebrate the 50th anniversary of the signing of Title IX legislation, which created almost immediate opportunities for the implementation of girls’ and women’s sports at the secondary and collegiate levels.

Many people reminiscing and discussing the impact weren’t even born in 1972.

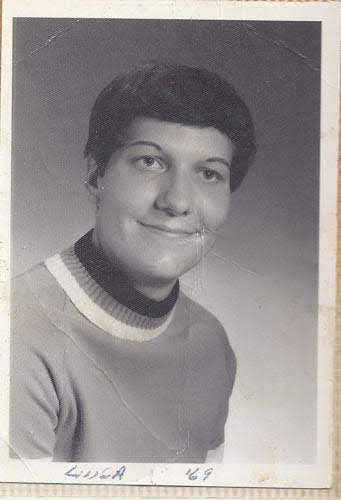

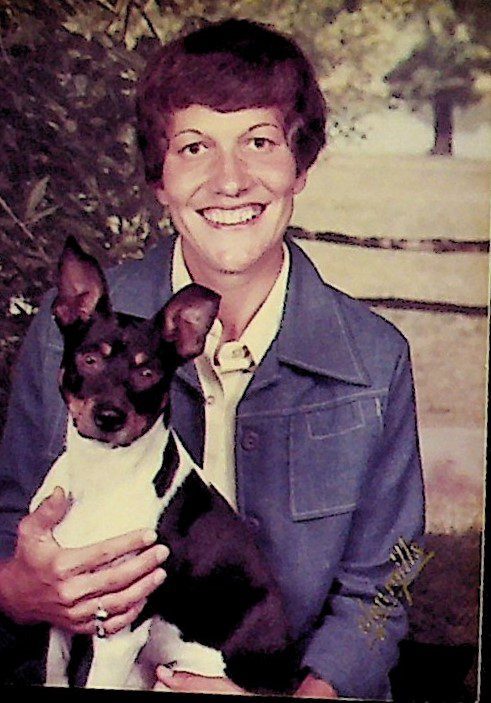

Oakwood High School graduate Linda Richter was part of the historic groundbreaking as girls’ sports were introduced at area high schools.

She was in her ninth year of teaching at Farmer City-Mansfield High School – now known as Blue Ridge – when the 1972-73 school year began.

The national Title IX mandate became official during the summer of 1972. Many high schools, however, were unprepared to offer girls’ sports that first year.

Farmer City-Mansfield was able to field a girls’ basketball team in Year 1.

Richter was the coach. The team played three games.

Richter doesn’t remember any complaints about the limited schedule.

“The girls were just happy to have sports,” Richter recalled. “They didn’t know they should have 10 or 15 games (to be more equal to the boys’ schedule).

“We didn’t have the strategy that you have today.”

The transition to adding an assortment of girls’ sports was not an easy one.

“It was a hard battle,” Richter said. “We had the same facilities (as before) and the guys thought they should have them all the time.”

She speculated that basketball was the first sport of choice to introduce Farmer City and Mansfield girls to athletics because, “it was so popular.”

Richter remembers some resistance, too.

“A lot of people didn’t want the girls in little shorts (like the boys wore at the time) out in front of people,” she said. “In the beginning, we didn’t have a uniform. It was an adaptation from P.E. classes.”

The concept of girls participating in sports was in existence well before Title IX. What changed was the manner in which contests were held.

“It started with GAA (Girls Athletic Association),” Richter said. “That was about all girls had, unless they were a cheerleader.”

Much of what was available for the teen-aged girls through GAA was intramural events at their own school.

“For a few years,” Richter said, “we had Play Days. We’d go to LeRoy, Heyworth or Unity and the girls got to participate. Usually they would play volleyball.”

Play Days had little resemblance to what would follow when interscholastic competition was permitted.

“If three schools were there (for a Play Day), the teams had to be mixed up,” Richter said. “You had to have one from each school.”

If badminton was the day’s activity, a doubles “team” would consist of one girl from Farmer City-Mansfield and one from LeRoy, for example.

The emphasis was on “play.”

Even before high schools started competing against one another in girls’ sports, Richter remembers two sports where there was an IHSA series for the females, but with no fanfare.

“In bowling, schools would go to their local centers and send in scores to the IHSA,” Richter said. “They would put the results together and let the schools know (the state placings), but there were no awards.

“They did the same with archery.”

The IHSA, though, does not acknowledge results from any girls’ sports before sanctioning came about through Title IX.

The IHSA first recognized a state champion in girls’ bowling for the 1972-73 school year.

The Title IX legislation got the ball rolling for girls, but there were challenges to overcome.

“I’d never had any classes in coaching (at Eastern Illinois University),” Richter said.

She had first-hand knowledge of some sports – field hockey, in particular – from playing, but she didn’t gravitate to the coaching assignments.

While she helped organize and enable the girls’ sports movement to gain steam at Farmer City-Mansfield, she was satisfied to spend many of her 35 years in the district as an assistant or working behind the scenes.

“After a few years (by the late 1970s), I started doing the scheduling for the girls, games and the officials,” Richter said. “The AD didn’t have much time for scheduling.

“I enjoyed those things. They took a lot of time, but I knew it was appreciated.”

One issue she faced while scheduling was the lack of phones at the high school.

“There were three phones,” Richter said, “one in the main office, one in the principal’s office and one in the men’s P.E. area.”

It was an unpaid position, but one which she embraced. The smiles on the faces of the high school girls were all she needed to see.

“They were so enthusiastic that they got to do anything,” said Richter, who started her tenure in the district in 1964 when it was known as Moore Township High School.

A consolidation with Mansfield in the summer of 1971 created Farmer City-Mansfield, which was in existence through the 1983-84 school year. When Bellflower was then added to the mix, the district became known as Blue Ridge.

Richter, who retired in 1999, was a prominent part of the district’s history in addition to overseeing the start of girls’ sports.

The first team – boys or girls – representing Farmer City (or its predecessor) to win a sectional championship was her field hockey team during the 1976-77 school year.

That team compiled a 10-1 record and lost in the state quarterfinals, 3-2, to New Trier, which had an enrollment 10 times greater than Farmer City-Mansfield.

The following year, another field hockey team coached by Richter also captured a sectional crown and reached the IHSA’s Final Four, where it again fell victim to a New Trier team, 1-0, in the state semifinals.

She felt well-supported.

“The community was behind it,” Richter said.

Field hockey was not a popular Downstate sport, which made scheduling regular-season games difficult.

“You had to be up by Chicago to get games,” Richter said.

Among the few available opponents in the central region of the state were Pana, Springfield Southeast and Tolono Unity.

It was something of a miracle, Richter said, that Farmer City-Mansfield even had a team.

“Under the stage was a whole bunch of field hockey equipment,” Richter said. “No one knew how it got there. It was surprising they had the equipment. The sticks are so expensive.

“I did a short session on it in P.E., and the kids enjoyed it.”

There was so much interest, she formed a high school team.

“I had 44 people come out and had to cut it to 22,” Richter said.

Because several of her players had other commitments (such as cheerleading) after school, Richter had to improvise on scheduling practices.

“Those girls came at 6 a.m. for practices,” she said.

The squad members quickly took ownership of the fledgling program.

“They put their names on the sticks,” Richter said.

To help subsidize their trips to state, the Farmer City-Mansfield girls did a fundraiser, selling Kathryn Beich candy. They generated enough money for the overnight stay in Chicago.

Though gym space was a perennial issue for indoor sports once the girls began participating, there were fewer hassles during the fall and spring.

“We had wonderful outside space,” Richter said. “We had a field hockey field marked for us by the football field. It was a job scheduling time when the activities came indoors.”

Not surprisingly, she said, “I still like field hockey.”

Richter, who lives in a home in rural Oakwood near where she was raised, celebrated her 80th birthday earlier this month.

As she reflected on her pioneer role in girls’ athletics, she also remembered how much else has changed.

“My first year teaching (1964-65), I made $3,000,” she said, “and we didn’t get paid for extra duties (such as taking tickets at a basketball game).

“Eventually we got $200 for extra duties, but that was for everything (whether a person did one or five).”

Her coaching resume included stints with basketball, bowling, field hockey, softball, tennis, track and field and volleyball.

“It makes me very proud,” Richter said. “It’s almost amazing and overwhelming. Something good came from my being a teacher.”

In addition to coaching, her duties – like many of her peers in the 1970s – also included taping ankles and wrapping legs.

Her background at Oakwood was one of the reasons for an interest in a variety of sports and activities.

“I had a good teacher in high school who made things interesting for us,” Richter said. “I liked to try everything.”

Her only regret is that more people don’t understand what life was truly like for girls prior to the signing of Title IX.

“Some people take things for granted,” Richter said. “I wish they knew how fortunate they were. A lot of schools didn’t have GAA (prior to Title IX).”

During the past 50 years, girls’ sports have evolved, but as Richter watches the progression, there is one thing that she notices.

“They are still evolving today,” she said. “I was hoping it would take off, but I never imagined it would be like it is now.”